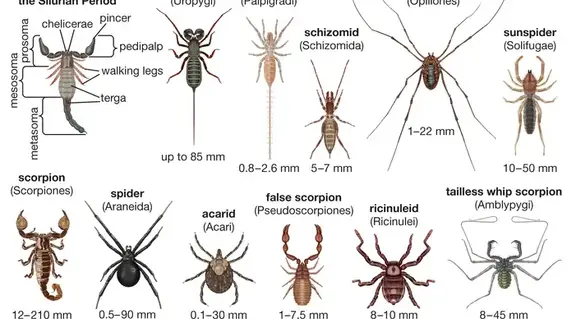

arachnid, (class Arachnida), any member of the arthropod group that includes spiders, daddy longlegs, scorpions, and (in the subclass Acari) the mites and ticks, as well as lesser-known subgroups. Only a few species are of economic importance—for example, the mites and ticks, which transmit diseases to humans, other animals, and plants.

Morphology[]

Arachnids range in size from tiny mites that measure 0.08 mm (0.003 inch) to the enormous scorpion Hadogenes troglodytes of Africa, which may be 21 cm (8 inches) or more in length. In appearance, they vary from short-legged, round-bodied mites and pincer-equipped scorpions with curled tails to delicate, long-legged daddy longlegs and robust, hairy tarantulas. Like all arthropods, arachnids have segmented bodies, tough exoskeletons, and jointed appendages. Most are predatory. Arachnids lack jaws and, with only a few exceptions, inject digestive fluids into their prey before sucking its liquefied remains into their mouths. Except among daddy longlegs and the mites and ticks, in which the entire body forms a single region, the arachnid body is divided into two distinct regions: the cephalothorax, or prosoma, and the abdomen, or opisthosoma. The sternites (ventral plates) of the lower surface of the body show more variation than do the tergites (dorsal plates). The arachnids have simple (as opposed to compound) eyes.

Internal Anatomy[]

The arachnid exoskeleton is formed of chitin, a nitrogen-containing carbohydrate associated with a protein. This complex results in a tough but pliable external skeleton. The exoskeleton consists of two parts, the thin outer epicuticle, which usually contains a wax and is impermeable to water, and a thicker endocuticle. Membranes, flexible portions of the cuticle, are present wherever there are articulations. Growth can occur only by shedding the old exoskeleton, a process termed molting or ecdysis. This process is under hormonal control and involves the secretion of a new cuticle below the old one. Hardening (sclerotization) may be accompanied by pigmentation.

Muscular System[]

The muscles of the cephalothorax are well developed, while those of the abdomen are reduced. The muscles are striated, similar to those of vertebrates. Muscles in the legs have their origin either on the endosternite or on the body wall and extend to the basal segments of the appendages. Muscles within the appendages make possible the movements of the individual segments.

Nervous system[]

The muscles of the cephalothorax are well developed, while those of the abdomen are reduced. The muscles are striated, similar to those of vertebrates. Muscles in the legs have their origin either on the endosternite or on the body wall and extend to the basal segments of the appendages. Muscles within the appendages make possible the movements of the individual segments.

Stimulus[]

There are commonly three types of sense organs: tactile hairs called trichobothria, simple eyes (ocelli), and slit (lyriform) sense organs. Specialized structures, possibly serving as tactile organs or detectors of air movements, include malleoli (racket organs) of sunspiders and comblike appendages (pectines) of scorpions. The number of simple eyes found on the carapace varies. Scorpions, for example, may have as many as five pairs of simple eyes on the sides of the carapace in addition to a median pair, while daddy longlegs have only median eyes, and many cryptic or cave-dwelling species have either reduced eyes or none at all.

Digestive system[]

With the exception of some daddy longlegs and mites, arachnids are carnivorous, relying upon smaller arthropods for their food. Most species partially digest their prey as it is held in the chelicerae. The digestive system is a tube that begins with the mouth, situated below the chelicerae, and leads into the pharynx, then into the esophagus, and from there into the sucking stomach, which has heavy muscles and serves to pump the partially digested food into the midgut, where special enzymes digest the food. The absorptive surface of the midgut is increased by a series of blind sacs (gastric caecae).

Respiratory system[]

Two types of respiratory organs are found among arachnids: book lungs and tracheae. Book lungs are found in hardened pockets generally located on the underside of the abdomen. Diffusion of gases occurs between the hemolymph circulating within thin leaflike structures (lamellae) stacked like pages in a book within the pocket and the air in spaces between these thin structures. The tracheal system consists of a number of tubes that open to the exterior by paired respiratory pores (spiracles) and is similar to that of insects. Diffusion of gases occurs within small fluid-filled tubes that ramify over the internal organs. Scorpions, tailless whip scorpions, and whip scorpions rely upon book lungs. Pseudoscorpions, sunspiders, ricinuleids, daddy longlegs, and mites and ticks have only tracheae.

Ecology[]

The numbers and predaceous habits of arachnids make them important to humans. Free-living mites play an important role in the conversion of leaf mold to humus. Many mites are parasitic, and many ticks are intermediate hosts for organisms that cause serious diseases. Though all spiders possess poison that can be utilized for subduing prey, only a few have a poison sufficiently powerful to affect humans. A bite of the black widow spider (Latrodectus mactans) may result in discomfort or serious illness, whereas that of the brown recluse spider (Loxosceles reclusa) may result in a severe local reaction, including tissue death. The sting of some scorpions may cause a severe reaction and even death.

Life Cycle[]

Reproduction[]

Indirect Sperm Transfer[]

In most cases the male does not transfer spermatozoa directly to the female but rather initiates courtship rituals in which the female is induced to accept the gelatinous sperm capsule (spermatophore). During mating the sperm are transferred to a sac (spermatheca) within the female reproductive system. The eggs are fertilized as they are laid. Mating in sunspiders is more active, occurring at dusk or during the night. During courting the male seizes the female, lays her on her side, massages her undersurface, opens her genital orifice, and forces a mass of sperm into her spermatheca. Reproductive behaviour in mites is highly variable; sperm usually are produced in a spermatophore and transferred to the female either by the chelicerae or, in ricinuleids, by the third pair of legs of the male.

Direct Sperm Transfer[]

The daddy longlegs appear to be the only arachnids in which sperm transfer is direct. There is little or no courtship among the members of this class. Instead, mating occurs whenever a male and female encounter one another. The male has a chitinized penis that is inserted into the genital opening of the female as the partners face one another.

Egg Development[]

Among scorpions the fertilized eggs develop inside the mother, and the young are born alive. In scorpions whose eggs contain much yolk, the eggs develop within the oviduct; in those with little yolk, the eggs remain in place, and each embryo lies in a diverticulum (hollow outpouching) with a tubular extension through which nutrient fluids pass from the wall of the maternal intestine. When the young are sufficiently developed, they are expelled and carried about on the mother’s back until after the first molt. False scorpions carry their eggs in a brood sac attached to the genitalia. The embryos develop and grow within this brood sac and are nourished by the female.

Nymphal Stage[]

Growth occurs by molting, or ecdysis. In many arachnids the first molt occurs while the animal is still within the egg. The newly hatched arachnid is small, and the exoskeleton is less sclerotized (hardened) than that of the adult. With the exception of the mites and ticks and the ricinuleids, which have three pairs of legs when hatched, the hatchlings have four pairs of legs. The number of molts required for attaining maturity varies considerably, especially among the larger species, which may molt up to 10 times. Before molting, arachnids seek a protected site. Most spiders, false scorpions, and some mites produce a cocoon to protect themselves at this time. Mites differ in both development and growth. In the life cycle of the mite, unlike other arachnids, an egg hatches into a six-legged, or hexapod, larva, which passes through one or several immature (nymphal) stages before becoming an adult. Most mites lay the eggs, though in some species the eggs develop within the body of the female and hatch within or immediately after extrusion (ovoviviparous). Some of the Acari are also able to reproduce from unfertilized eggs (parthenogenesis). The life cycle of ticks is similar to that of mites.

Behavior[]

Movement[]

Locomotion among arachnids involves moving the first and third legs of one side and the second and fourth legs of the other side forward nearly simultaneously. Most arachnids are not great travelers. Those that do cover long distances rely upon methods other than walking or running. For example, small spiders about to migrate will scale vertical objects, release a strand of silk, and rely upon the wind to carry them away (ballooning).

Feeding Habits[]

As predators, most arachnids feed chiefly upon smaller arthropods, although exceptions are found among parasitic ticks and mites and plant-feeding daddy longlegs and mites. Ticks and mites are nourished principally by fluids obtained either from living animal or plant material or from decaying organic matter. Parasitic forms have mouthparts modified for sucking blood or juice. Daddy longlegs appear to be the only arachnids capable of ingesting small particles.

Social Interactions[]

Though most arachnids are solitary animals, some spiders live in enormous communal webs housing males, females, and spiderlings. Most of the individuals live in the central part of the web, with the outer part providing snare space for prey shared by all the inhabitants. In some cool and dry areas, daddy longlegs often gather in enormous numbers, probably protecting themselves against extremes of temperature or desiccation.

Identification Features[]

Though arachnids are easily recognized by the division of the body into two parts, the cephalothorax (prosoma) and abdomen (opisthosoma), and their possession of six pairs of appendages, they are extremely diverse in form. The dorsal region of the cephalothorax has a solid covering called the carapace, and the underside has one or more sternal plates or the coxal (basal) segments of the six pairs of appendages.